|

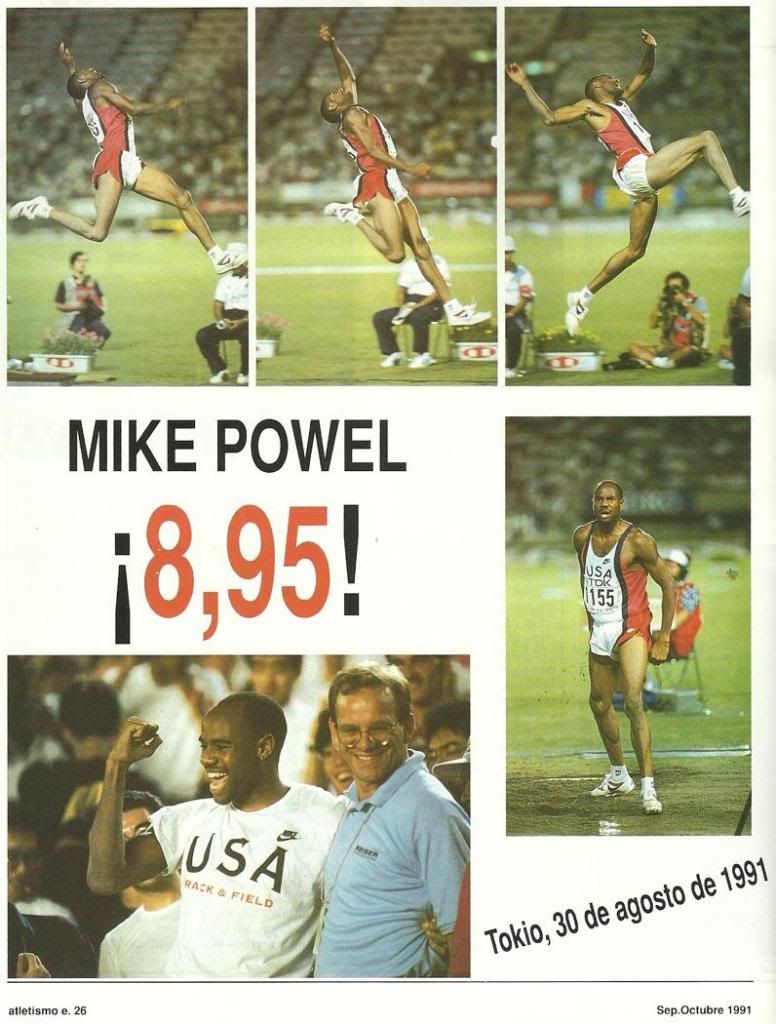

| Mike Powell's greatest day From the magazine "Atletismo español", Sept-Oct 1991 http://media.photobucket.com/image/mike%20powell%20tokyo/Piropillos/MikePowell895Tokio91_AE.jpg |

Sorry I keep on saying it: thanks to Eurosport for broadcasting the last World Championships; otherwise in Spain

I just like travelling to better times. The inaugural edition of the World Championships in Athletics was one of the most celebrated sportive outings of 1983. In the field events we had the privilege of beholding the first major victory of two of the best jumpers (and sportsmen) of the 20th Century: Sergey Bubka and Carl Lewis. Can you imagine a live broadcasting offering just recorded highlights of an event which has Bubka or Lewis taking part in? The “high-flying Ukrainian” would go on to win 6 world consecutive crowns, thus being the titleholder for no less than 16 years, besides becoming Olympic champion in Seoul 6 meters with the pole vault and achieved a more than remarkable 35 world records in the discipline. The “son of the wind” would become one of the most decorated athletes in history with 8 world and 9 Olympic titles, at 100, 200, 4x100 meters and long jump. In the latter discipline he won the gold medal in 4 Olympic Games, something which only he and discus thrower Al Oerter have accomplished in a single athletic event. However, while Bubka set 35 world bests, Lewis, who everybody for many years pointed out as the man to beat the mythic Bob Beamon’s 8.90 record, could never reach this target. Furthermore, he would have to witness how another jumper, Mike Powell, carry this glory, which had been predestined for him ever since the single day he was born. Last 31st August was the 20th anniversary of this historical feat at the 1991 Tokyo World Championships, at arguably the best long jump competition ever, where Powell needed to overcome Beamon’s record to get to beat Lewis for the first time in his life.

The long jump has traditionally been one of the most emblematic events in Athletics, maybe because of holding some of the most emblematic world records in sport. In 80 years, only five men have been able to jump beyond the previous best. The first of them, the legendary Jesse Owens, became in 1935 the first athlete in breaking the 8 metres barrier (8.13 exactly), just the previous year of his four gold medals landmark at Berlin Olympic Games, before the astonished gaze of Hitler, who believed in the superiority of the Aryan race. No less than 25 years were needed for further improvement. Eventually, another Afro-American, Ralph Boston, went to 8.21. Boston and Soviet Union representative, Igor Ter-Ovanesyan, would take turns in adding steadily some centimetres to the record, reaching 8.35 by 1965 and 1967 respectively. Then came the unforgettable Mexico Olympic Games with the unbelievable jump of Bob Beamon, who landed in the far end of the pit and needed a manual measurement, because the optical device installed with this purpose had not been designed to cover such incredible distance: 8.90!!! When Beamon realized about his feat, he collapsed to his knees and placed his hands over his face in shock, having to be helped to his feet by his competitors. It suggested to physiologists he had somehow summoned all the superhuman strength which ordinarily comes upon people only in disasters. (1)

Amazingly, among this exclusive club of record beaters, only the ones with the most modest exploits, Ralph Boston and Ter-Ovanesyan, could follow a long successful career. Jesse Owens was suspended as he tried to obtain some economical benefits from his talent, in a time Athletics was just understood as an amateur sport, and from then on could challenge only horses. Anyway, the II World War put a long hiatus to any Olympic dream. Bob Beamon’s big jump was not a fluke: he had already reached 8.33 outdoors and went on that same 1968 year to an 8.30 indoor world record, which was not improved until 1980 and still stands into the all-time lists. Yet he would not jump further than 8.22 for the rest of his career. His gigantic 8.90 had killed the athlete and the event itself. No one could try to get reasonably close to this distance in many years, including the same Beamon. (2)

|

| Bob Beamon competing indoors in 1968 http://blogs.diariovasco.com/index.php/airelibre/2010/10/24/quien_mato_a_bob_beamon Watch BEAMON's WORLD RECORD here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEt_Xgg8dzc |

Amazingly, among this exclusive club of record beaters, only the ones with the most modest exploits, Ralph Boston and Ter-Ovanesyan, could follow a long successful career. Jesse Owens was suspended as he tried to obtain some economical benefits from his talent, in a time Athletics was just understood as an amateur sport, and from then on could challenge only horses. Anyway, the II World War put a long hiatus to any Olympic dream. Bob Beamon’s big jump was not a fluke: he had already reached 8.33 outdoors and went on that same 1968 year to an 8.30 indoor world record, which was not improved until 1980 and still stands into the all-time lists. Yet he would not jump further than 8.22 for the rest of his career. His gigantic 8.90 had killed the athlete and the event itself. No one could try to get reasonably close to this distance in many years, including the same Beamon. (2)

Eventually, the new indoor record holder Larry Myricks and Lutz Dombrowski achieved marks over 8.50. It was the first sign Bob Beamon was not from another planet and one day humanity would be able to close the gap. Dombrowski can be easily considered one of the most talented long jumpers ever. A pity his country’s boycott to Los Angeles Olympic Games deprived us from what should had been a stellar duel against Lewis. Besides, the East German 8.54 winning jump at 1980 Moscow Olympic Games had been done without the aid of altitude. Mexico 2240 meters had proved optimal for sprint and jump performances. Stunning world records were set almost in every event. Especially ideal were the conditions enjoyed by Bob Beamon, who was jumping into the rarefied thin atmosphere just previous to a rainstorm and counted with the maximum allowable wind in his favour (+2.00 m/sec). As an indication, Lee Evans in the same hour ran the 400 meters distance in a time of 43.86, which was not improved until 1988. In successive years athletes would try to take advantage of similar conditions and thus Pietro Mennea or Joao Carlos de Oliveira respective records at the 200 meters and triple jump were also accomplished at altitude.

Nevertheless, the new kid in town in the long jump was reluctant to this mode. He stated he did not want to see an “A” after his marks and even refused competing in some outings held at altitude. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1961, Carl Lewis , under the masterful guidance of Tom Tellez, first at the University of Houston, then as a member of Santa Monica Track Club, dominated the event in a way never seen before, since his 1981 breakthrough. That year he overcame Dombrowski’s low-altitude best, flying to 8.62, then improved to 8.76 and8.79 in successive years. No wonder for someone always jumping at sea level, his still standing indoor world record, set in his highly successful 1984 year, would match his outdoor best. He was equally dominant in the sprints and by 1983 he also owned the low-altitude best at 100 (9.97) and 200 metres (19.75). He would not care too much about other athletes achieving better marks, as soon as he could beat them when it mattered most, as he would do at Helsinki-83 Worlds before Calvin Smith or at Rome-87 before Robert Emmiyan, who previously in the year had landed just 4 centimetres short of Beamon.

This is maybe why Carl Lewis was such sensational an athlete. In his prime, he would never run a bad race and was rarely defeated, especially at the big occasions, where he always showed his best. There was a moment Ben Johnson seemed to have reached a superior level, but this episode ended badly for the Canadian, who would recognise his massive use of steroids. Enraged, Lewis would show in the next major championship, inTokyo Tokyo

Carl Lewis wanted to become the most famous, admired and richer sportsman who ever lived (3) and he did not fell far away from his ambitious targets. The IOC named him Olympian of the century and so did Sports Illustrated magazine, which curiously in Lewis’ most accomplished seasons had chosen instead Mary Decker (1983) and Edwin Moses and Gymnast Mary Lou Retton (1984) as sportsmen of the year. For me it does not make too much sense to decide whether Lewis, Mark Spitz, Mohamed Ali or Nadia Comaneci was the best, with every one practising a different sport and living in different circumstances. It stands also for athletics and the comparison with Moses is illustrative: The hurdler was also unbeaten for more than 10 years and even with a superior winning streak (107 finals and 122 races overall). However he was less lucky in his Olympic curriculum and thus could only won two titles: he missed one chance because of theUS boycott in Moscow

Carl Lewis knew he was talented enough to have a place in the history of sport, alongside two of the most charismatic athletes ever: he dreamed with matching Jesse Owens’ four gold medals in a single Olympic Games and beat the record of records, held by Bob Beamon. He succeeded brilliantly in his first target at Los Angeles-84 and was not far from do it again in Seoul-88, but Joe DeLoach had the better of him at the200 metres and the American relay squad dropped the baton in the heats. His second target was achieved instead by Mike Powell. Powell, from Philadelphia

|

| Carl Lewis running in full speed http://listas.20minutos.es/lista/los-mejores-deportistas-de-la-historia-96152/ |

Nevertheless, the new kid in town in the long jump was reluctant to this mode. He stated he did not want to see an “A” after his marks and even refused competing in some outings held at altitude. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1961, Carl Lewis , under the masterful guidance of Tom Tellez, first at the University of Houston, then as a member of Santa Monica Track Club, dominated the event in a way never seen before, since his 1981 breakthrough. That year he overcame Dombrowski’s low-altitude best, flying to 8.62, then improved to 8.76 and

This is maybe why Carl Lewis was such sensational an athlete. In his prime, he would never run a bad race and was rarely defeated, especially at the big occasions, where he always showed his best. There was a moment Ben Johnson seemed to have reached a superior level, but this episode ended badly for the Canadian, who would recognise his massive use of steroids. Enraged, Lewis would show in the next major championship, in

Carl Lewis wanted to become the most famous, admired and richer sportsman who ever lived (3) and he did not fell far away from his ambitious targets. The IOC named him Olympian of the century and so did Sports Illustrated magazine, which curiously in Lewis’ most accomplished seasons had chosen instead Mary Decker (1983) and Edwin Moses and Gymnast Mary Lou Retton (1984) as sportsmen of the year. For me it does not make too much sense to decide whether Lewis, Mark Spitz, Mohamed Ali or Nadia Comaneci was the best, with every one practising a different sport and living in different circumstances. It stands also for athletics and the comparison with Moses is illustrative: The hurdler was also unbeaten for more than 10 years and even with a superior winning streak (107 finals and 122 races overall). However he was less lucky in his Olympic curriculum and thus could only won two titles: he missed one chance because of the

Lewis interest in making money helped athletics become a professional sport and overcome the hypocritical amateurism conception, from which Jesse Owens had been a victim. However things took an unexpected twist when Lewis was turned down a contract by Nike because of his flamboyant clothes and flat-top haircut: “If you are a male athlete I think the American public wants you to look macho” (4) Owens had suffered from the racism of his time, having to have lunch or be lodged in restaurants and hotels just for blacks, when competing with the American team. Beamon had been involved in the same controversy, refusing to compete against Brigham Young University Boston

|

| Jesse Owens competing at Berlin Olympic Games http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/42/Jesse_Owens1.jpg |

Carl Lewis knew he was talented enough to have a place in the history of sport, alongside two of the most charismatic athletes ever: he dreamed with matching Jesse Owens’ four gold medals in a single Olympic Games and beat the record of records, held by Bob Beamon. He succeeded brilliantly in his first target at Los Angeles-84 and was not far from do it again in Seoul-88, but Joe DeLoach had the better of him at the

Despite his achievements, the Philadelphia Houston University

Powell was a very emotional jumper. He was unable to control his nerves when competing and it was a huge hindrance for him and even needed to search the help of a psychologist. He often got just two or three valid jumps in competition so he was called by his mates “Mike Foul”. Indeed he had a quite respectable number of long foul attempts, one of them near the 9 metres line. His final results were not really talking about his real potential. On the other hand, Lewis always stayed cool and was able to coordinate flawlessly run, approach and takeoff for a perfect jump. The Santa Monica Huntington 100 metres ) working specially the technique of every phase of the jump. He said in the last two steps the athlete must arrived with flat-foot and hips upright for an optimal take-off and the landing must be done with the heels not with the body. (6)

That evening Tokyo

However, the defending champion was performing astoundingly. Always approaching perfectly the takeoff line, he went to the longest jump of his life (8.83, though wind aided), and improved again in his fourth leap to 8.91: beyond Beamon! But again the wind (+2.9 m/sec) invalidated his record. In between, Powell got a narrow foul in the 8.80 region. At this stage of the competition the eternal bridesmaid was increasingly enraged, feeling “the way you do when you are about to get into a fight” (5). He had lost too many opportunities in his career and did not felt like failing again the same way. He took the runway with determination and this time around, in his 5th attempt, his emotive temper played in his favour: Finally he achieved the perfect jump he had inside of him and the officer measured it 8.95 (+0.3). The ultimate record had been surpassed!!

Nevertheless, he had not won the competition yet. Lewis had two tries left and he was not the one who gives up. Again King Carl responded with another massive jump (8.87), into a slight headwind, a new PB, but not enough. Still one more chance: Powell bent to the ground, praying, not wanting to see his rival final attempt: he was sure Lewis was to deliver a9 metre jump… Yet he did not: he had landed 8.84 metres beyond the board to close his best competition ever. The “son of the wind” had been eventually beaten the day he accomplished the fourth best jumps of his whole career. (7) He put an arm over the winner’s shoulder briefly not daring to look at his face. Powell, overjoyed, started to celebrate, giving a hug to the board officer, then to Coach Huntington, then to every Japanese spectator around. He also tried to hug Lewis but the beaten champion just took his bag and left the stadium visibly disappointed. He would never be the man who broke Beamon’s world record.

|

| Ralph Boston jumps 8.34, a new world record, in 1964 in Los Angeles http://www.corbisimages.com |

However, the defending champion was performing astoundingly. Always approaching perfectly the takeoff line, he went to the longest jump of his life (8.83, though wind aided), and improved again in his fourth leap to 8.91: beyond Beamon! But again the wind (+2.9 m/sec) invalidated his record. In between, Powell got a narrow foul in the 8.80 region. At this stage of the competition the eternal bridesmaid was increasingly enraged, feeling “the way you do when you are about to get into a fight” (5). He had lost too many opportunities in his career and did not felt like failing again the same way. He took the runway with determination and this time around, in his 5th attempt, his emotive temper played in his favour: Finally he achieved the perfect jump he had inside of him and the officer measured it 8.95 (+0.3). The ultimate record had been surpassed!!

Nevertheless, he had not won the competition yet. Lewis had two tries left and he was not the one who gives up. Again King Carl responded with another massive jump (8.87), into a slight headwind, a new PB, but not enough. Still one more chance: Powell bent to the ground, praying, not wanting to see his rival final attempt: he was sure Lewis was to deliver a

Observers said technique was decisive in Beamon’s triumph. (8) Despite his last six strides speed in his winning jump had been 39.38 Km/h , to 40.53 km/h in Lewis longest attempt, his performance was flawless; meanwhile Lewis had some technical imperfections as too low hips prior to his takeoff. Beamon had hit the sand right with his feet. Lewis did it with the butt, but Powell with a last move in the air pulled his upper body to the right so he landed with his legs. King Carl, who had carried for years a deserved reputation of egotist and arrogant did not want to accept his defeat: “I had the greatest series of all time. He had just one jump. He may never do it again” (5)

Carl Lewis took a minor revenge, defeating Powell narrowly at the following year Olympics (8.68 to 8.64). Then the new world record holder defended his crown in Stuttgart 9 metres and his leap was wrongly considered foul, what is also stated about Carl Lewis when he was just a newcomer. (3) The most decorated jumpers of the moment, Dwight Phillips and Irving Saladino, have also failed to deliver a jump superior to 8.74. Mike Powell’s world record is now twenty years old and is likely to stand longer than Jesse Owens’s and Bob Beamon’s. Maybe in the future two other long jump giants will be born to deliver another exciting match comparable to the one we had the chance to watch one day between Carl Lewis and Mike Powell.

(2) http://blogs.diariovasco.com/index.php/airelibre/2010/10/24/quien_mato_a_bob_beamon

(3) http://joeposnanski.blogspot.com/2011/08/30-foot-jump.html

(3) http://joeposnanski.blogspot.com/2011/08/30-foot-jump.html